Vault #23: Quarantine Kangaroo

The Truth and Fiction Surrounding Angel Island’s Animal Detainees

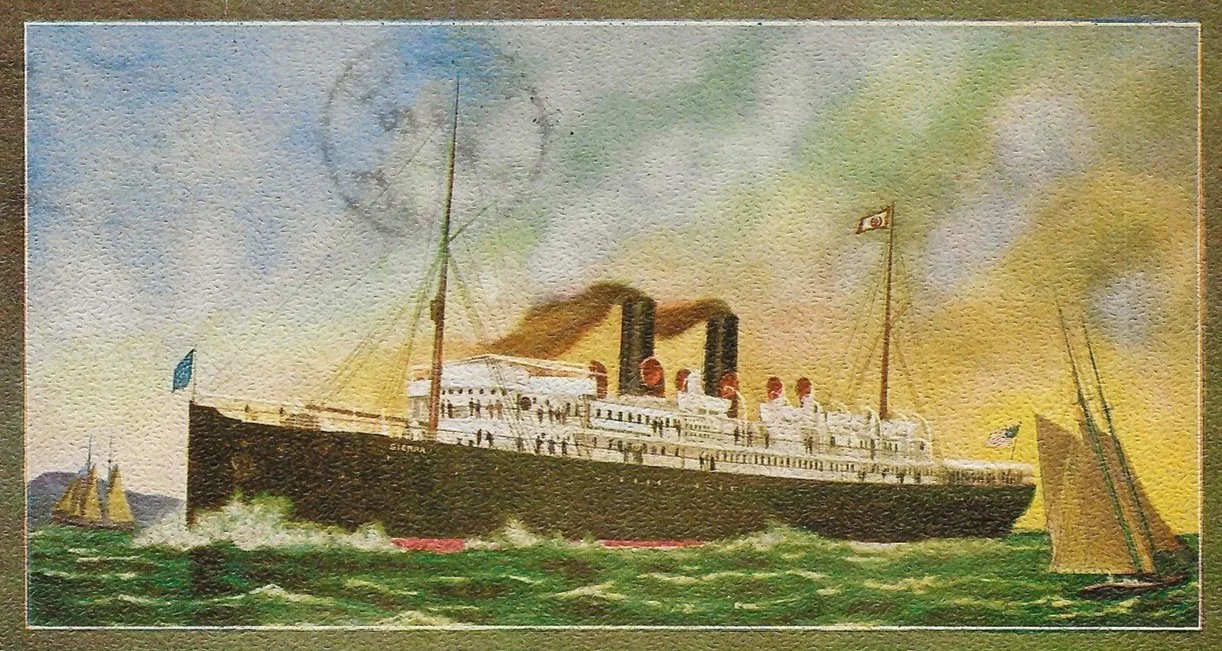

The two stories involving kangaroos on Angel Island also reference the ships that transported them: the SS Ventura and SS Sierra, sister ships that operated regular routes between Sydney and San Francisco. These passenger ships played a key role in trans-Pacific migration, transporting immigrants, cargo, and live animals from the South Pacific to San Francisco from 1900 through the 1920s. The image above shows the Sierra en route to Honolulu in 1912. Photo credit: This image is in the public domain. Link to original.

Before the immigration station opened in 1910, Angel Island remained largely inaccessible to the residents of San Francisco. When news did emerge from the government’s outposts on the island, it often made local headlines, offering rare glimpses into the otherwise mysterious and sometimes surprising, tragic, or unusual events unfolding on the remote island.

In 1891, the United States government established a quarantine station on the island’s north shore. This facility, consisting of forty buildings, was designed to disinfect clothing and baggage, isolate individuals exposed to contagious diseases, and prevent the spread of infection to the mainland population. As trans-Pacific travel increased at the turn of the century, the quarantine station became a vital component of the nation’s public health strategy, even if local residents did not fully understand its operations or purpose.

At the same time, San Francisco was emerging as a major international port city. The Spreckels family launched the Oceanic Steamship Company, which began facilitating passenger routes between San Francisco and the Antipodes—namely Australia and New Zealand—as early as 1900. These steamships carried not only immigrants and commercial goods but also live animals, such as kangaroos, which occasionally became entangled in quarantine and immigration protocols or appeared in newspaper reports.

The two articles featured below recount specific incidents in which kangaroos were caught up in the evolving systems of quarantine and immigration enforcement in San Francisco Bay. Although these stories were originally written for entertainment, they also served to demystify the government’s expanding presence on Angel Island.

Learn more about the history of the Angel Island Quarantine Station by visiting Vault #25: Hospital Cove.

The Questioning of Mr. and Mrs. Kangaroo

In May 2025, a video posted to Instagram depicted a kangaroo holding a boarding pass while a gate agent questioned a woman nearby. Though the clip was later revealed to be AI-generated, it echoed themes from a satirical newspaper article published 120 years earlier. Both the contemporary video and the 1905 article used humor to show how society often treats outsiders as unwanted or dangerous.

On August 28, 1905, The Salinas Index Journal published a satirical story about a kangaroo family caught in a routine inspection aboard the SS Ventura. The article—titled “Kangaroo Immigration”—reflected the public’s growing fascination with kangaroos in the early twentieth century and satirized the policies of quarantine and immigration enforcement.

At the time, kangaroos were regularly shipped through San Francisco en route to zoos across the country. Circuses and vaudeville theaters also featured boxing kangaroos as novelty headliners, while the public embraced a broader cultural trend: the “kangaroo walk” circulated around the Bay Area, kangaroo leather goods became fashionable, and kangaroo cutlets were served as a delicacy at locations like the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco.

Just one day prior, on August 27, 1905, the San Francisco Call published a photo of Golden Gate Park’s newly arrived kangaroos. Their sudden appearance in the local press likely inspired the satirical piece that followed in The Salinas Index Journal the next day.

For clarity and accessibility, the article has been adapted for a modern audience. The original can be viewed here (page 3, column 4).

KANGAROO IMMIGRATION

Federal Officials Enforcing the Law with Severity.

The kangaroo family was headed for a new life in California. They heard America was “the land of the free,” but when their ship pulled into San Francisco Bay, things didn’t go as expected. Even though their tickets were paid for and they hadn’t broken any laws, the family was stopped before they could hop off the ship.

They wondered why others like Bob Fitzsimmons and Tim Murphy—famous boxing kangaroos—were never detained or deported. But now, this family of peaceful kangaroos were being treated like criminals.

Bob Fitzsimmons Jr., mentioned in the article, was a red kangaroo named after the famed professional boxer Bob “The Fighting Blacksmith” Fitzsimmons. Known simply as “Bob Jr.,” the kangaroo performed regularly on the vaudeville circuit until his retirement from boxing in 1916. Following his career, he lived out his remaining years at Milwaukee’s Washington Park Zoo. The image above, taken at Coney Island in 1915, shows Bob Fitzsimmons alongside his namesake kangaroo, “Fitz.”

As soon as their ship anchored, an immigration officer climbed aboard. He didn’t waste any time. “Got any money?” he asked. Mrs. Kangaroo dug through her pocket, but instead of cash, out popped a couple of baby kangaroos.

“Smuggling, huh?” the officer remarked. “Let me check that pocket. You could be hiding a prizefighter in there.”

It was an insulting thing to say, but Mrs. Kangaroo stayed calm. She let the officer see for himself. But when they thought the worst was over, the officer said, “If I let you in, you’ll probably end up as public charges.”

Mr. Kangaroo tried to reason with him. “Please let us stay. Bob Fitzsimmons will help us out.”

Mrs. Kangaroo had had enough. She spun toward Mr. Kangaroo and shouted, “Oh, cut the chatter!” Then—BAM!—she hit him with a classic Tim Murphy punch. He went down for the count, while the baby kangaroos yelled, “Fake! Fake!” Just like the crowd at an old boxing match.

Mrs. Kangaroo gave the officer a sharp look, but he didn’t flinch. “What makes you think you won’t end up depending on the government?”

“We can jump our bills,” she answered proudly. “We pay them.” That seemed to satisfy him, but he wasn’t done. “Where’s your health certificate?” he asked. “For all I know, you could have the plague.”

The family didn’t have any paperwork, but Mrs. Kangaroo explained that the only health issue was the babies teething. “And if you don’t believe me,” she said, “climb up on a stepladder and let me kick your hat off.”

But the officer wasn’t taking any chances. Even though President Roosevelt had promised everyone a fair shot in America, the officer shook his head. “You’re going into quarantine,” he said. “Ten days on Angel Island. You might be healthy, but you’re responsible for that kangaroo walk, and I can’t allow that on my watch.”

-

An immigration officer is a government official responsible for reviewing the paperwork and legal status of individuals entering the United States. These officers ensure that travelers meet the requirements for admission and determine whether further inspection or detention is necessary.

-

A public charge is a term used to describe someone who is likely to rely on government assistance for basic needs such as food, housing, or medical care. If immigration officers believed someone arriving in the US had no money, no job prospects, or would be unable to support themselves, they could be labeled a public charge and denied entry.

-

When people in the early 1900s talked about the plague, they usually meant bubonic plague, a deadly disease that occurred in San Francisco between 1900 and 1904. People who showed signs of the disease—like fever, swelling, or weakness—had to be quarantined to keep the illness from spreading.

-

The “kangaroo walk” was a term used in the early 1900s to mock people who moved awkwardly or unnaturally in public. It was a term used to describe a stiff, exaggerated way of walking. Characteristics of the walk included arms that hung limp or motionless, while the chest and chin were thrust forward.

Behind the Story

The SS Ventura arrived in San Francisco from Sydney via Honolulu on August 21, 1905. Although quarantine station journals do not mention kangaroos among the cargo, they do record the death of an Italian woman from typhoid fever during the voyage. Her husband, who exhibited symptoms consistent with bubonic plague, was placed under observation. As a precautionary measure, the ship’s crew and all steerage-class passengers were detained on Angel Island until their release on August 29.

The Haunting of the Quarantine Station

Angel Island State Park presented the following kangaroo story with live musical accompaniment by the Del Sol Quartet on October 4, 2024. A 45-minute recording of the performance is available on the California State Parks’ YouTube channel here.

Two years after the “Kangaroo Immigration” article made headlines, a second story again connected kangaroos to Angel Island. An article titled “Discovers Devil of Angel Island” was published in The Maitland Daily Mercury on August 19, 1907. It tells of a night watchman who became convinced he was being followed by a ghost during his rounds. The mysterious figure turned out to be a real-life kangaroo.

The story, told in a suspenseful and humorous style reminiscent of Mark Twain or Ambrose Bierce, describes how an employee of the quarantine station was alarmed by eerie nighttime sounds and unexplained movements. Only later did Dr. Trotter uncover the truth. “Just as I was going to give it up,” he recalled, “I was startled by a big gray animal jumping out of the brush in front of me. It was a kangaroo.”

It is through Dr. Trotter’s revelation that readers learn the kangaroo had been living undetected on the island for nearly 14 months.

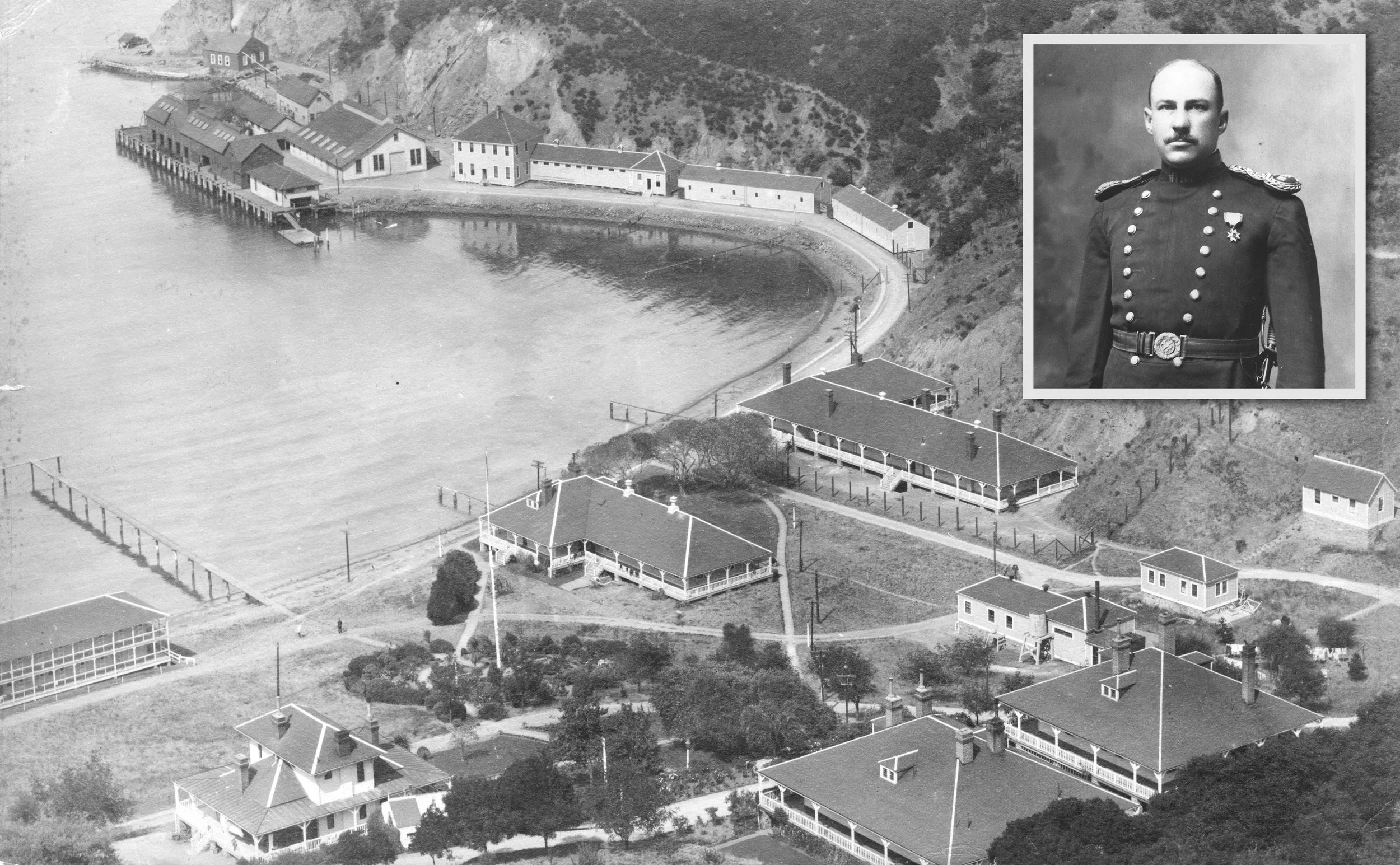

This aerial view shows the quarantine buildings on Angel Island as they appeared in 1911. Today, passenger ferries arrive at Ayala Cove, which was once the site of the US Quarantine Station—then known as Hospital Cove. The inset image features Dr. Frederick Trotter, who is referenced in the article. He served on Angel Island until 1912, when he was reassigned to a post in Honolulu. Photo credits: National Library of Medicine.

The following article is presented without edits or corrections.

DISCOVERS DEVIL OF ANGEL ISLAND.

An Australian Kangaroo.

To Dr. Trotter of the quarantine service belongs the honour of discovering the “devil” of Angel Island and setting at rest the fears of the attendants at the quarantine station, who had become firmly convinced that the island was haunted (says the San Francisco “Chronicle”).

Night-Watchman Flannagan was the first to be followed by the mysterious presence. His duty is to go the rounds of the various buildings at the station at regular intervals during the night. At these times he carries a lantern, and formerly he found the job a congenial one. Flannagan’s light flitting from house to house about the station had always been a signal of safety to the sleepless, who chanced to look out of the windows of the hospital when he was on his rounds. His equipoise was disturbed some weeks ago, however, when he realized that he was being followed.

No ordinary footfalls would have disturbed the watchman, but these were the sounds of no human steps. When he stopped the strange sounds were stilled also. Thinking it was all in his imagination, he started again, only to hear the ghostly “ka-plunk, ka-plunk” at regular intervals, following his steps. This was too much for the nerves of Flannagan, and he fled to the officers’ quarters with the cry that the devil was after him. They laughed at Flannagan, but next morning strange tracks were found on the sand beside the footprints of the watchman.

The next night Flannagan was fearful when he lit his lantern and started on his rounds. Nothing happened until he reached the remote smallpox compound. It was a misty night, and very still. As he rounded the corner, he was terrified to hear the ghostly “ka-plunk” just behind him. Running back with his lantern held over his head, Flannagan saw a figure outlined in the fog, which seemed to rise from the ground and disappear.

“I’ve seen the devil this time, sure,” Flannagan told the doctors, after he had rushed back to the quarters. “And sure, he lifted himself off the ground till he was 10 feet tall, and then, with two jumps, he was over the top of the hill.”

The next morning everyone turned out to hunt the “devil.” Dr. Trotter found his trail and tracked it over the hill into the brush.

“Just as I was going to give it up,” says the doctor, “I was startled by a big gray animal jumping out of the brush in front of me. It was a kangaroo. How he got on the island was a mystery until we found that when the Sierra was quarantined last summer a cage of kangaroos had been brought ashore and held at the station until we were sure they were not infected with the smallpox. Two of them escaped. As they had never been seen, it was supposed that they were dead. It was Flannagan’s devil, sure enough.”

The kangaroo continues to keep out of sight in the day, but nightly, when Flannagan starts on his rounds, he hops after the man with the lantern, doing the rounds with the watchman.

-

The story refers to a remote smallpox compound on Angel Island. This was possibly the island’s old “detention camp,” where individuals with highly contagious diseases were isolated from other passengers. The camp was built in the 1890s near the future Angel Island Immigration Station. When the story was published, the federal government was actively constructing the station, a project that relied heavily on mule labor. The mule enclosure may have provided a potential source of food, water, or shelter for the escaped kangaroo.

In 1913 and 1914, two isolation hospitals were built on the hillside above the quarantine station. Passengers diagnosed with smallpox would have been held there while being treated. Both hospitals were built six years after the article was published, making the site a less likely location for the kangaroo.

-

There are several species of kangaroo. The Red Kangaroo (Macropus rufus) is the largest of all kangaroos and is commonly associated with the iconic image of the “boxing kangaroo.” However, in the story, Dr. Trotter described seeing a “big gray animal,” which suggests it was likely an Eastern Grey Kangaroo (Macropus giganteus).

The Eastern Grey is one of the largest kangaroo species, capable of weighing up to 152 pounds and reaching a total body length of over 6 feet 7 inches, including the tail. Like other kangaroos, it is primarily nocturnal and feeds on a range of grasses and shrubs. Its size and color aligns with Dr. Trotter’s description, making Macropus giganteus the most likely candidate.

-

Yes. Historical records confirm that a variety of animals were detained on Angel Island as part of efforts to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. One documented case occurred in 1933, when twenty-five parakeets and thirty-two parrots were held due to concerns over psittacosis, commonly known as “parrot fever.”

Another unusual case involved a pet goat named William Harrison Bones, affectionately called “Billy Bones.” The goat belonged to Henry L. Stimson, who served as Governor-General of the Philippines from 1927 to 1929 and later as US Secretary of State. In 1929, Billy Bones arrived in San Francisco en route to Washington, DC, but was detained on Angel Island for several weeks. Quarantine officers initially decided to return the goat to Manila due to regulatory concerns. When Stimson learned of the situation, he personally intervened, ultimately securing Billy’s release. A photograph of Stimson’s goat can be seen here.

Behind the Story

Dr. Frederick Trotter mentioned “a cage of kangaroos” was held at the Angel Island Quarantine Station during the summer of 1906. As referenced in the story, the SS Sierra did report a case of smallpox on board. On May 21, 1906—just one month after the devastating San Francisco earthquake—the Sierra was held in quarantine. Doctors vaccinated the cabin passengers and stewards, disinfected the ship’s interior, and eventually cleared the vessel for landing. However, as with the 1905 account, the quarantine station journals do not mention kangaroos being removed from the ship.

Four days after the Sierra’s kangaroos were supposedly sent to quarantine, a severe storm struck the island. A journal entry on May 25 indicates the damage was extensive, and they “spent the day all hands putting things to rights.” The storm is what likely led to the kangaroos’ escape. Unfortunately, no additional records have been found to clarify the animal’s fate after its discovery by Trotter a year later.

Antipodean. The Great Frank C. Bostock Trained Wild Animal Arena and Jungle. The "Bostock" Souvenir Postal Card Program. With Postcard of Fitz the Boxing Kangaroo. www.antipodean.com/pages/books/20003/ny-coney-island-kangaroo/the-great-frank-c-bostock-trained-wild-animal-arena-and-jungle-the-bostock-souvenir-postal-card?soldItem=true

Imperial Valley Press. "Bill Bones to Enter Country," July 12, 1929.

National Library of Medicine. Journals of the United States Quarantine Station, Angel Island, 1903 to 1943.

OnMilwaukee. “Nevermind Samson - What about Bob?,” November 23, 2012. https://onmilwaukee.com/articles/bobthekangaroo.

Salinas Index Journal. "Kangaroo Immigration," August 28, 1905.

San Luis Obispo Daily Telegram. "Kangaroo Meat is the Very Latest," January 30, 1909.

The Maitland Daily Mercury. "Discovers Devil of Angel Island. An Australian Kangaroo," August 19, 1907.