America’s Western Gateway

Between 1870 and 1940, more than 25 million immigrants arrived in the United States, with a major peak in annual arrivals between 1900 and 1914, when nearly 900,000 persons came per year on average. Those arriving in San Francisco, especially Asian immigrants, encountered very different legal regimes and social circumstances than those passing through Ellis Island in New York. On the West Coast, immigration was mediated through racial exclusion, restrictive legislation, and the US government’s attempt to control Pacific migration. These forces made Angel Island (opened in 1910) into a notorious station of detention and exclusion as well as arrival.

Early Chinese Migration and Exclusion

By the mid-19th century, immigrants from Guangdong Province in southern China began arriving in California, driven by famine, rebellion, and economic collapse. Initially welcomed as laborers during the Gold Rush and railroad boom, they soon became scapegoats when the economy faltered in the 1870s. Politicians and labor leaders exploited anti-Chinese sentiment, passing local and state laws that restricted where Chinese immigrants could live and work.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first federal law to restrict immigration on the basis of nationality and race. This act halted nearly all Chinese labor immigration and set a precedent for later laws excluding immigrants from other parts of Asia. Over the following decades, these laws created a system of racialized enforcement that reshaped US immigration policy nationwide.

Journeys Across the Pacific

Despite exclusionary laws, immigrants continued to cross the Pacific. The voyage from Asia to California could take three weeks or more, often stopping in Honolulu, Manila, Yokohama, Shanghai, or Hong Kong. Outside of China, immigrants from over 80 countries came to San Francisco, including individuals from India, Japan, Russia, the Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, Latin America, and Pacific Island nations.

By the late 1930s, several hundred Jewish refugees in Europe fled Nazi persecution by crossing Russia to East Asian ports. From there, they boarded ships to San Francisco. Many were detained upon arrival in the United States because they lacked sufficient funds to continue to their final destinations. Their stories represent the global scope of Angel Island’s history.

Processing and Detention on Angel Island

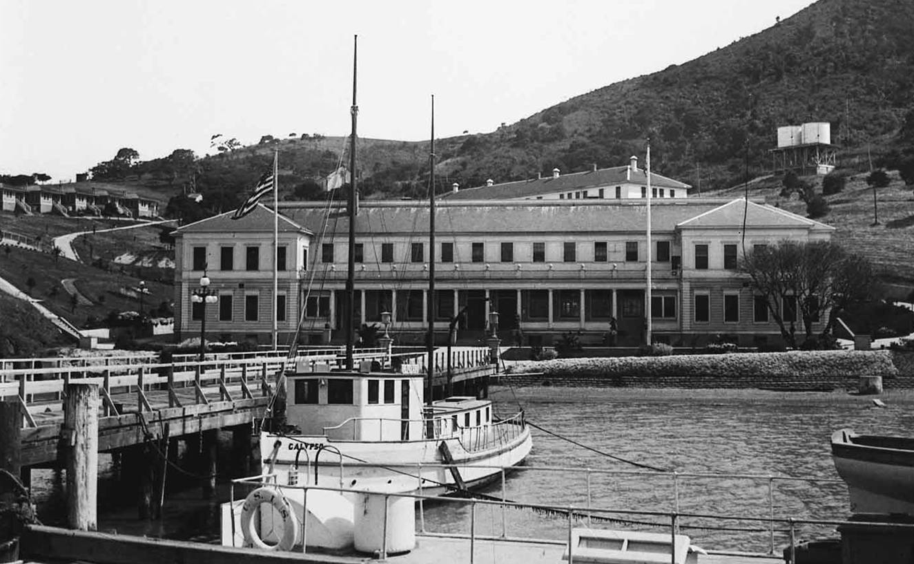

Opened on January 21, 1910, the Angel Island Immigration Station was designed to detain, rather than welcome, newcomers. The Bureau of Immigration—predecessor to today’s USCIS—chose the island for its isolation, believing it would prevent detainees from escaping or communicating with friends and relatives in San Francisco.

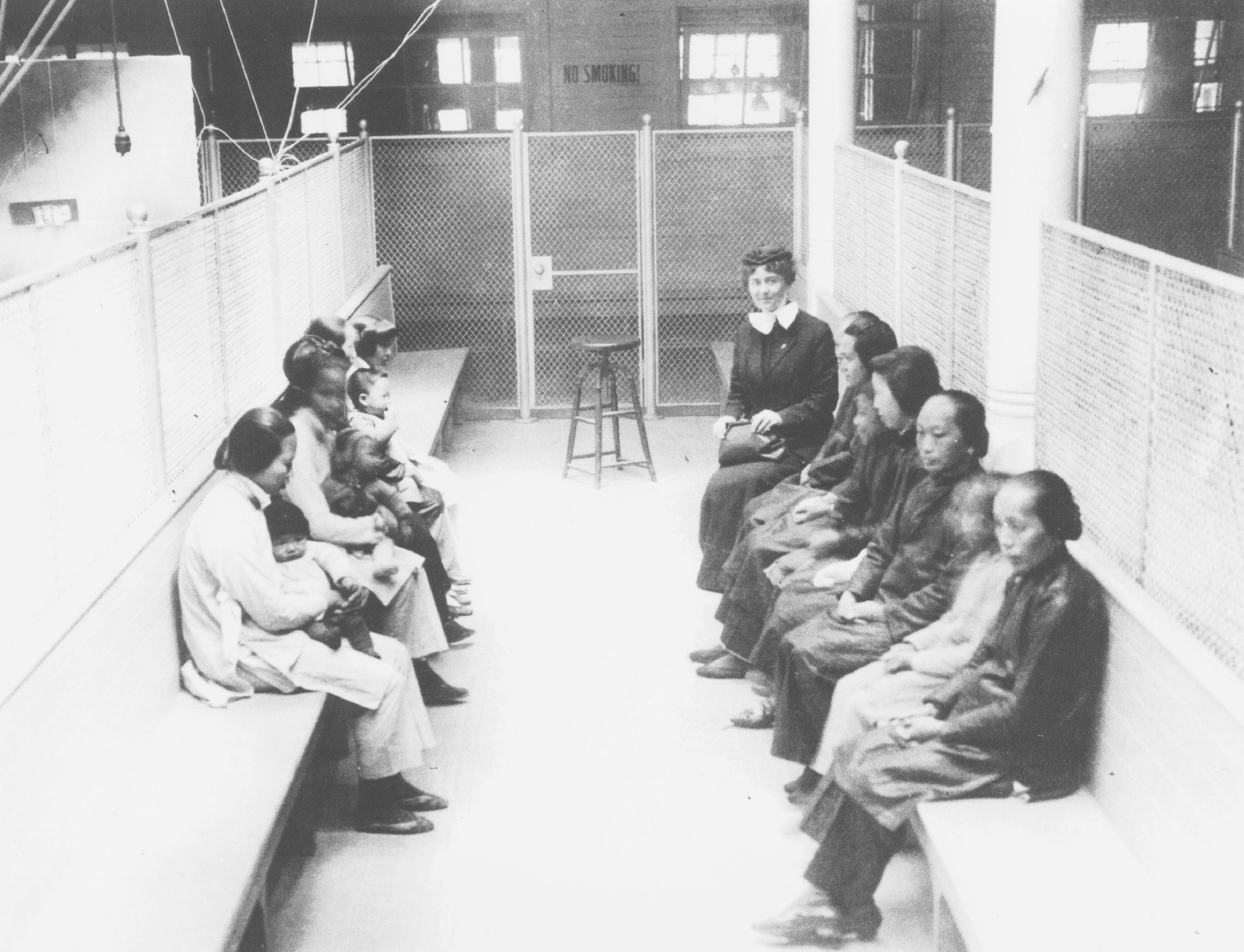

Upon arrival, passengers were separated by race, gender, and class. European and first-class travelers were usually processed aboard ship and allowed to disembark immediately. Asian and Pacific Islander immigrants, particularly those in steerage, were ferried to Angel Island for invasive medical inspections and interrogations. The first stop for all immigrants was the administration building. There, inspectors and doctors placed immigrants through a series of tests to determine whether they could land in the United States.

Interrogation and “Paper Sons”

Under the Chinese Exclusion Act, only a few Chinese—merchants, teachers, students, diplomats, clergy, and dependent children—were allowed to enter the United States legally. After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire destroyed immigration records, some Chinese residents claimed to have dependent children living overseas. To assist others in China, and to financially benefit from the government’s lack of historic records, false identities were sold to families who hoped to send their sons or daughters to America. Each “paper child” received a detailed personal history that they could memorize and use on Angel Island.

Immigrants endured exhaustive interrogations before the Board of Special Inquiry, answering numerous questions about their supposed family, neighbors, and village layouts to verify their claimed identity. Any inconsistency between an applicant and their witness could mean rejection or deportation. Some waited weeks, others years, for the board’s decision on their cases. For Chinese detainees, the fear of exposure persisted for years. They were sometimes forced to live as their paper identities indefinitely.

Decline and Reuse

In August 1940, the station’s administration building burned down, destroying many records of the immigration service. All remaining detainees were moved to mainland facilities, and the immigration station formally closed in October the same year. During World War II, the site briefly housed Japanese internees and prisoners of war. After the war, it was abandoned and fell into disrepair.

Rediscovery and Restoration

By 1970, the site was nearly forgotten. That year, California State Park Ranger Alexander Weiss discovered hundreds of Chinese poems carved into the wooden walls of the abandoned barracks—haunting records of confinement, loneliness, and defiance. Weiss’s discovery inspired community action. Chinese American activists formed the Angel Island Immigration Station Historical Advisory Committee (AIISHAC), laying the foundation for preservation efforts.

In 1976, the state legislature allocated funds to restore the barracks. The Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation (AIISF) was later established to continue preservation and educational work. The site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1997, and major restorations in the 2000s stabilized the structures and created new exhibits. The Angel Island Immigration Museum (AIIM), housed in the restored hospital building, opened in 2022.

Legacy

Today, Angel Island stands as a testament to both exclusion and resilience. It tells the story of how race, policy, and geography shaped immigration on the Pacific Coast. Through continued efforts by AIISF and California State Parks, the site now serves as a place of remembrance and dialogue, ensuring that the experiences of those detained here, and the broader legacy of immigration in America, are never forgotten.

California State Parks and the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation wish to thank the following contributors whose generosity made possible the completion of Phase One of the restoration of the US Immigration Station, Angel Island.

A Save America's Treasures federal grant, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior; Save America's Treasures at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, including major support from: The Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, Marin Community Foundation, The J. Paul Getty Trust's Preservation Planning Fund, and Ms. Yeni Wong; The National Trust for Historic Preservation through: American Express Partners in Preservation program, in partnership with the American Express Foundation, The Cynthia Woods Mitchell Fund for Historic Interiors, and The Johanna Favrot Fund for Historic Preservation; California Cultural and Historical Endowment; California Parks Bond Act of 2000, Gee Family Foundation, Wallace Alexander Gerbode Foundation, Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund, Walter and Elise Haas Fund, and J.T. Tai & Company Foundation.

Additional Funders

Thomas & Eva Fong Family Foundation, Ken Lee Family Foundation, Lawrence Choy Lowe Memorial Fund, and Look Lowe Family Trust.

With special appreciation to the following

Angel Island Immigration Station Historical Advisory Committee, Architectural Resources Group, California State Parks Foundation, California State Senator John Burton, Donald Bybee, Chris Chow, Paul Chow, Phillip Choy, Ruth Coleman, Charles Egan, Erika Gee, Nicholas Franco, Forrest Gok, Elizabeth Goldstein, Dave Gould, Tod Hara, Daniel Iacofano, Kathy Lim Ko, Kimball Koch, Daphne Kwok, Him Mark Lai, Erika Lee, Newton Liu, Wan Liu, Felicia Lowe, David Matthews, Dale Minami, Ray Murray, Brian O'Neill, National Archives-San Francisco, Francelle Phillips, Daniel Quan Design, Danita Rodriguez, Douglas Tom, Katherine Toy, Kathy Owyang Turner, Xing Chu Wang, Connie Yung Yu, and Judy Yung.