Vault #25: Hospital Cove

An Introduction to the Angel Island Quarantine Station

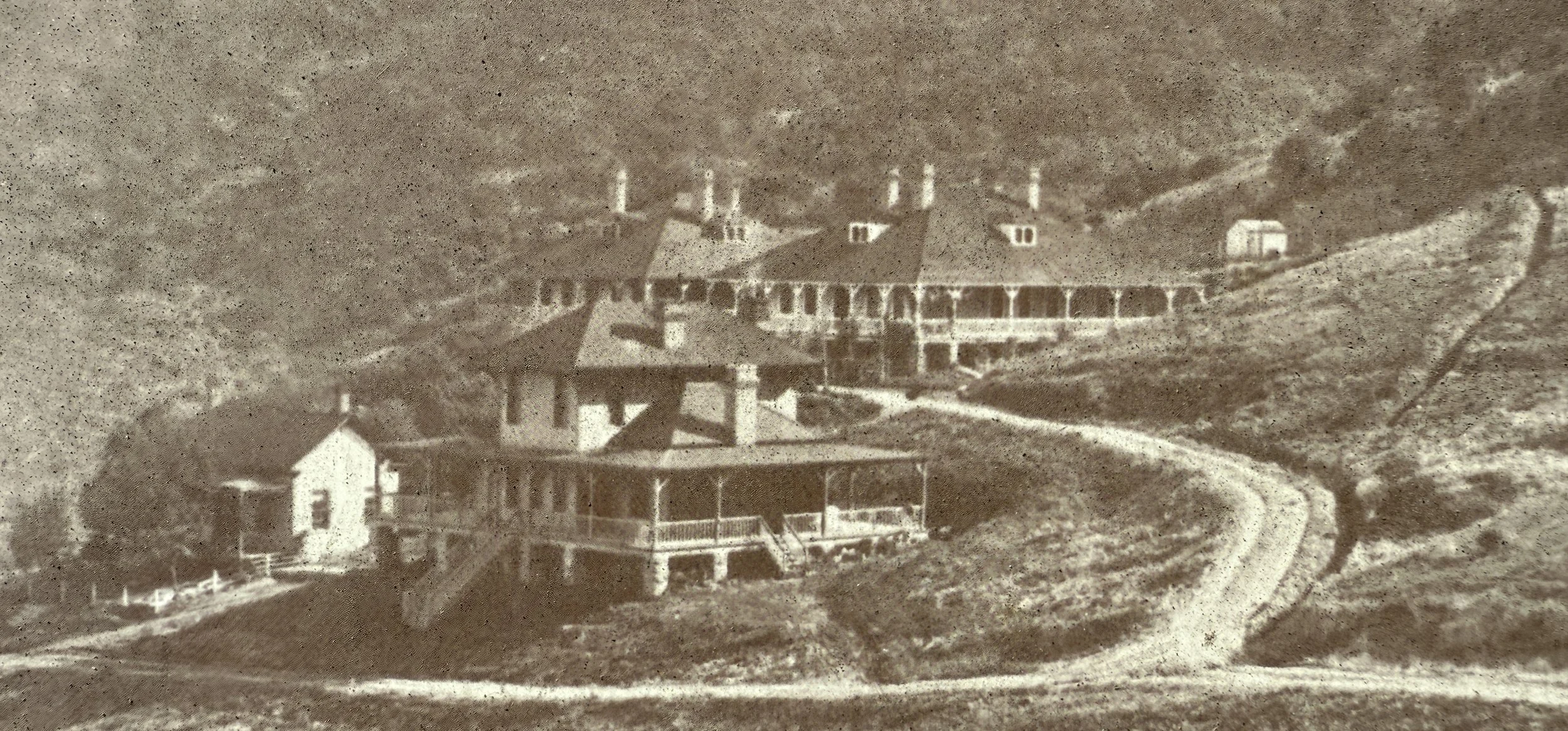

This view of the Angel Island Quarantine Station was taken in 1911, two decades after its opening in 1891. Following its closure in 1946, the area formally known as “Hospital Cove” was renamed “Ayala Cove.” Its namesake, Juan Manuel de Ayala, was a Spanish naval officer who, in August 1775, became the first European to successfully sail through the Golden Gate. While creating the first map of San Francisco Bay, Ayala named the island Isla de Los Ángeles—the Island of the Angels—known today as Angel Island. Photo credit: California State Library (2014-4522).

Before it became the location of an immigration station, Angel Island already had a facility for immigration inspection and control. The Angel Island Quarantine Station, established in 1891, served as the first line of defense against infectious diseases entering San Francisco from foreign ports. When the Angel Island Immigration Station opened on the island in 1910, the two facilities operated side by side for more than three decades. Trans-Pacific steamships anchored offshore for medical inspection, and passengers showing signs of highly-contagious illnesses were taken to Hospital Cove for treatment or isolation.

Together, Angel Island’s quarantine and immigration stations determined the fate of thousands of immigrants arriving in San Francisco Bay. One assessed the body, the other their right to belong. The stations’ proximity to one another reveals how federal policies shaped who was permitted to enter the United States and under what conditions.

Today, little remains of the island’s former quarantine station. The site once known as Hospital Cove, now Ayala Cove, functions today as Angel Island State Park’s primary point of arrival and departure.

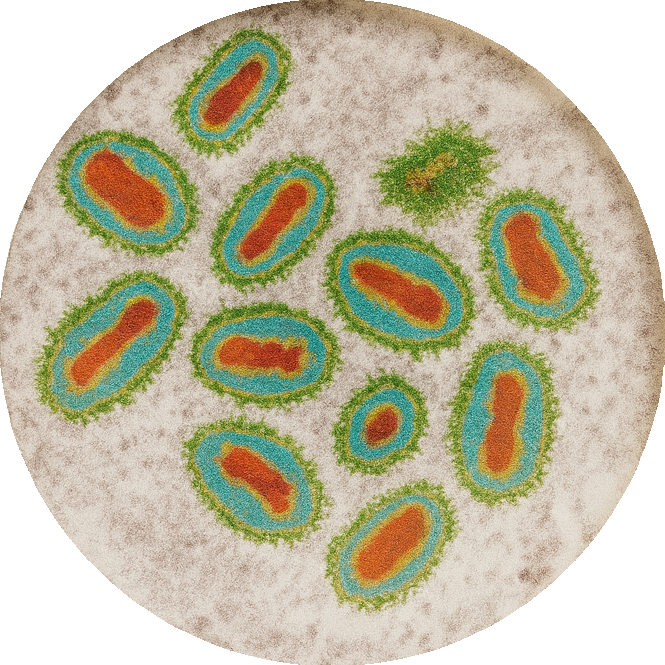

Quarantinable Diseases

This photograph shows the Millen Griffith arriving at the quarantine station in 1895. Tugboats, like the one seen here, transferred immigrants from steamships to Angel Island. Photo credit: National Library of Medicine.

San Francisco was the site of two of the most alarming public health crises in American history—the bubonic plague outbreaks of 1900-1904 and 1907-1908. Arising in Chinatown, the epidemic provoked panic, racial scapegoating, and a prolonged fight between the Chinese community, city officials, and the US Public Health Service. The epidemic, and the racial backlash that accompanied it, was chronicled in the PBS American Experience documentary Plague at the Golden Gate.

Over time, the Angel Island Quarantine Station became known as America’s first line of defense against highly transmissible diseases on the West Coast. Its officers inspected vessels, disinfected cargo, and examined passengers to prevent the plague and other contagions from reaching San Francisco.

A list of quarantinable diseases appeared in an issue of The Pacific Pharmacist, dated May 22, 1913.

“The diseases are small-pox, plague, leprosy, cholera, yellow fever, and typhus fever. Plague and cholera are the two diseases of special importance to the port of San Francisco as this is the mostly likely point of entry of these highly contagious and infectious diseases.”

The Public Health Service also had the responsibility of inspecting imported animals as well as a ship’s passengers and crew. You can learn more by visiting Vault #23: Quarantine Kangaroo.

Inspection & Disinfection

The Public Health and Marine Hospital Service operated a small quarantine station near today’s Fisherman’s Wharf. An article published in Overland Monthly in January 1907 gives this location a brief description. “The sally-port of the quarantine station is at Meiggs Wharf, at the foot of Powell street, and is termed the Boarding Station.” The photo shows the cutter Golden Gate (of the US Customs Service) next to the boarding station. Photo credit: San Francisco Public Library.

Before ships were cleared to dock, quarantine officers conducted an inspection of the passengers, crew, and cargo. If a disease was detected on the ship, they would disinfect the ship’s quarters, cargo, and baggage to eliminate disease. To learn more about this process, visit Vault #5: Keepers of the Gate.

Inspection

The Pacific Pharmacist offered a succinct account of what immigrants experienced during their initial inspection aboard the ship. The article describes how quarantine officers examined arriving passengers for signs of illness and determined which vessels required disinfection before entering port.

“Entering vessels… are approached on their entrance to San Francisco harbor and boarded by the quarantine officers. The ship’s log is inspected and inquiry made concerning the health conditions and deaths, if any, during the voyage. The passengers and crew are then examined. They are formed in line, about six feet apart, and walk slowly toward the inspecting officer who judges by the general appearance, facial expression and other characters of the presence of disease. Special attention is given to the hands, wrists and forehead as here the first signs of smallpox are manifest. Should there be [any] doubt in the mind of the physician during this hasty inspection, the passenger is detained for a more rigid examination.”

In this 1931 photograph, Dr. Joseph Bell (left) of the Public Health Service stands with quarantine workers holding fumigation equipment. During ship disinfections, cyanide gas was released to exterminate disease-carrying pests. Before reboarding, officials carried live mice—if the mice survived, it was considered safe for the crew to return. Photo credit: National Library of Medicine.

This photograph shows the USS Omaha anchored at Hospital Cove in 1896. Originally built as a sloop-of-war for the US Navy in 1867, the Omaha was later decommissioned and transferred to the Marine Hospital Service. It was used to fumigate ships arriving in San Francisco Bay. The Omaha remained in service until its retirement in 1915. Photo credit: National Library of Medicine.

Disinfection

Dr. Hugh Cumming, the officer in charge of the Angel Island Quarantine Station from 1901 to 1906, published an article in the California State Journal of Medicine, recounting the first ship held at the island and the quarantine officers’ role in fumigating ships entering the bay.

“Opened April 29, 1891, the first vessel treated was the China, which arrived on December 20th, 1891, with smallpox on board. No sanitary inspection or disinfection of vessels was done by the Federal authorities, these being made by the city quarantine officer who was appointed by the Governor… Not all vessels quarantined should be, or are, subjected to such disinfection throughout… Here the quarantine officer must use his own judgment, uninfluenced by ignorant or malicious criticism, or by the natural desire of the vessel’s owners to avoid delay and expense, or by an unreasonable desire to be absolutely sure of a perfectly aseptic vessel. It is his duty to disinfect, when reasonable doubt exists after consideration.”

Treating Passengers

Kingland Smith described the sterilizer building as follows: “I saw the disinfecting plant where our trunks, handbags and other belongings had been shut up for 16 hours exposed to formalin gas at a temperature of 120 degrees Fahrenheit. There are three large fumigators 7.5 by 40 ft. They are like boilers and have a track on which the loaded trucks are run into them.” Photo credit: Myron Mason Family Collection.

Immigrants arriving in San Francisco faced three possible paths. Some were released directly from their steamships to the city after a brief inspection. Others were transferred to the immigration station, where they faced legal examination and questioning. Those believed to have been exposed to serious contagious diseases were first detained at the quarantine station for observation and, if cleared, transferred to the immigration station for further processing.

In an article published in The Northwestern Miller on January 27, 1904, trade correspondent Kingland Smith documented his experience in quarantine. Smith arrived aboard the SS Nippon Maru in October 1903. Doctors discovered a case of the bubonic plague onboard, which prompted a mass transfer of passengers and crew to Angel Island. In his account, Smith describes the quarantine procedure in detail.

Transfer to the Island

“Packages such as bedding were unceremoniously thrown down [to the tugboat]… But when it came to bringing table ware, silver and glasses, the boys were very careful, and the steep descent was made on a ladder by boys carrying a whole tray full of smashables on their heads... One poor little canary bird was tossed over, cage and all, from the Nippon to a man on the upper works of the tender... the canary fluttered wildly but seemed none the worse for its unusual journey, though its supply of bird-seed was scattered to the winds of heaven...

About noon we got away and went over to the quarantine dock, where our Chinese stewards had a busy time unloading.”

Photo credit: Kingland Smith.

Stop 1: Wharf Shed

“We waited around on the dock for a time not knowing just what was coming. Finally a man appeared with some bags of jute, like rather coarse grain bags, and told us to put a change of clothing in these to wear after we came out of the bath...

When at length all passengers had prepared their bundles, the bags were put on a truck and sent to the disinfecting chamber (click for image)… In the dock shed were large signs directing you to separate your things into two piles putting articles that would be injured by steam apart from the rest. The signs indicated that certain articles would be treated by steam and others by dry gas.”

Photo credit: Myron Mason Family Collection.

Stop 2: Bath House

“The baths are shower baths, 14 in number. Opposite each bath is a dressing room. (click for image) You take your bag of disinfected clothes [treated with formalin] in with you and after the bath you put these on and put the clothes you have worn in the bag. You are supposed to make a complete change, underwear, shoes, hat and all…

The odor of formalin was pretty strong in the bath and some of the passengers complained that it hurt their eyes. I did not find it particularly disagreeable. Sometimes disinfectants are put in the bath water, but in our case this was not considered necessary.”

Photo credit: Kingland Smith.

Stop 3: Quarters

“The rooms resemble staterooms on a large river steamer. They are lighted by electric lamps and heated by small steam coils and they have washstands with hot and cold running water, so they are very comfortable and moreover they were very neat and clean.*

Our period of quarantine was short, for we spent but one night on Angel island… The Chinese and Japanese are kept in separate buildings. All the ship’s crew were taken off the Nippon… only a watchman and the quarantine officials (click for image) being left aboard.”

Photo credit: National Library of Medicine.

*Smith is describing the station’s second-class or cabin passenger quarters. Accommodations for steerage and Asian passengers were separate and notably less comfortable.

Stop 4: San Francisco

“I hunted out my belongings from the various articles of luggage that were strewn around the shed in picturesque confusion. Passengers were idling about and killing time as best they could. One lady had been patiently sitting on her trunk for at least an hour when the tug came to fetch us.

We were taken to San Francisco on a revenue tug and the customs officials took our declarations on the way. It is about five miles from the quarantine to San Francisco... A few minutes later we were at the Pacific Mail wharf struggling with the San Francisco customs inspectors…”

Photo credit: Kingland Smith.

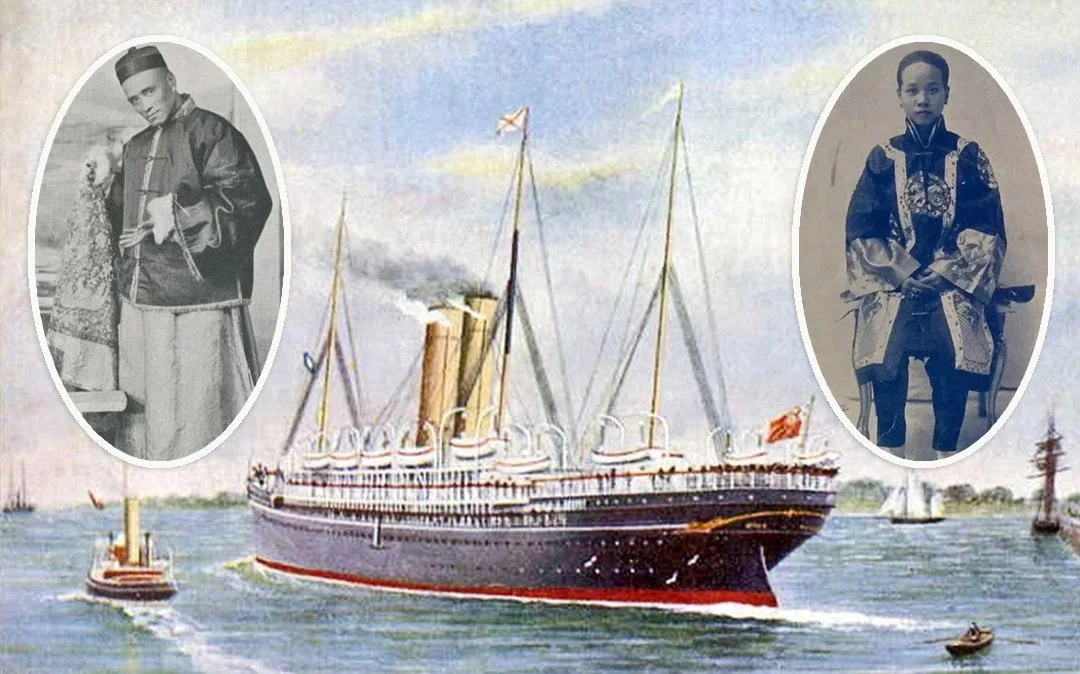

Ching Ling Foo & Chee Toy

The 1912 arrival of magician Ching Ling Foo and his daughter Chee Toy shows that even famous travelers from Asia were not exempt from inspection. Like other immigrants, they were subject to the same quarantine checks before being allowed to enter San Francisco.

A chief pharmacist’s mate inoculates a man from an unknown illness. Angel Island doctors often provided vaccinations to passengers to prevent the spread of disease. Photo credit: California State Parks.

The following article details the arrival of Ching Ling Foo, a world-famous magician, and his daughter Chee Toy aboard the SS Nile. Their story was published in the San Francisco Call on November 12, 1912.

“Dr. F.H. Cookingham, the liner’s surgeon, reported two cases of smallpox… The passengers were landed at the quarantine station, where they were vaccinated. Everybody received an antiseptic bath and the passengers clothes and personal effects were given a Russian bath in the big sterilizers… Among the passengers on the Nile is Ching Ling Foo, the Chinese vaudeville performer. Ching is a magician and for years has been one of the highest paid entertainers on the vaudeville circuit. He is accompanied by his fifteen year old daughter, Chee Toy, who is said to be a wonderful singer…”

Another article—published the same day—by the San Francisco Examiner also reported on their arrival.

“Chee Toy… a Chinese opera singer and protege of Oscar Hammerstein, the New York impresario, and her father, Ching Ling Foo, a noted Chinese actor, had to submit to the inconvenience of quarantine when a case of smallpox was discovered aboard the Pacific Mail liner Nile yesterday. Garbed in richly embroidered Oriental costume, Miss Toy and her Chinese poodle were ready to walk down the gangplank of the Nile, when the vessel arrived off Meiggs wharf from China yesterday morning, but Dr. Glover… ordered the vessel held at the Angel Island station for the night. The young songbird insisted that she and her father and twelve members of their troupe be permitted to land and, when a ship’s officer blocked the gangway with his arm, Miss Toy shed tears.”

The experiences of Ching Ling Foo and Chee Toy underscores the strict protocols that governed entry into San Francisco, where the quarantine station’s authority outweighed an immigrants social standing.

Mapping the Site

This is a composite map showing current and former structures at the former US Quarantine Station, Angel Island. Two historic maps were referenced in its creation: a quarantine area map from 1913 and an island “master map” from 1942 (revised in 1946). The building locations and the circulation routes are approximate. Some buildings were removed prior to the 1913 survey, while the function of other buildings changed over time. Click here to see a labeled photograph of Hospital Cove in 1911. Photo credit: AIISF.

-

Chief Surgeon’s Quarters (currently private residence)

Assistant Chief Surgeon’s Quarters (currently abandoned)

Greenhouse & Tool Room

Pharmacist’s Quarters (currently private residence)

Attendants’ Quarters AKA “White House”

Upper Hospital / Lazaretto

Lower Hospital / Lazaretto

Cabin Passenger Barracks

Attendants’ Quarters, Dining Room, & Kitchen (currently Angel Island State Park Visitor Center)

Paint Shop & Storeroom

Quarters for Cook & Waiter

Pump House (plus 12A)

Administration Building & Second-Class Passenger Barracks

Japanese Barracks

Laboratory

(removed by 1913)

(removed by 1913)

Chinese Barracks

Chinese Barracks

Attendants’ Quarters & Cabin Passenger Bath House

Sterilizer Building / Disinfecting House

Wharf Shed

Steerage Class Bath House (1913); Storerooms (1946)

Boat House

Carpenter & Machine Shop

Stable

Unknown

Power House (plus 28A)

Chinese Kitchen & Dining Room

Isolation Hospital (infected passengers)

Isolation Hospital (exposed passengers but not ill)

(removed by 1913)

(removed by 1913)

(removed by 1913)

(removed by 1913)

Surgeon’s Washing & Change House (not located on map)

Laundry

(Removed before 1913)

Chinese Kitchen & Junk Room (removed before 1946)

Wagon Shed (1913); Paint Shop (1946)

(removed by 1913)

Toilet House for Chinese Barracks

Men’s Toilet

Women’s Toilet

Blacksmith & Tool Shed

(removed by 1913)

(removed by 1913)

Steerage Barracks

In 1957, after California State Parks assumed control of the former quarantine station, all but five of the site’s historic buildings were demolished. This image shows an intentional fire set to several of the structures. Photo credit: San Francisco Public Library.

The quarantine station contained as many as 48 buildings and support structures during its 55-year history. Like the immigration station, it strictly enforced racial and class segregation. The site maintained separate lodging and facilities for the following groups of passengers:

Cabin (#8, 20): Merchants, diplomats, government officials, missionaries, and affluent tourists.

Second-Class (#13): Middle-income travelers, merchants, artisans, teachers, and students.

Steerage (#23, 48): Immigrant laborers, farmers, domestic workers, and family members.

Chinese (#18, 19, 29, 39, 42): Chinese travelers were often targeted as “high risk” by quarantine officials, regardless of their health.

Japanese (#14): Japanese travelers were treated more favorably than Chinese, but they were still scrutinized.

In this undated photo of the quarantine station, three employee residences can be seen. In the foreground is the pharmacist’s quarters (built in 1893). Seen behind is the chief surgeon quarters and assistant chief surgeon’s quarters (both built in 1890). Not pictured is the attendants’ quarters, dining room, and kitchen (built in 1935).

Today, of the five historic buildings saved from demolition, only four remain: the chief surgeon’s quarters (#1), assistant chief surgeon’s quarters (#2), pharmacist’s quarters (#4), and attendants’ quarters, dining room, and kitchen (#9). The fifth structure, the boat house (#24), no longer exists. Before #9 reopened, the boat house temporarily served as a visitor information center.

The Cove Today

Ayala Cove remains as active today as it was in 1891, when the quarantine station first opened. Several modern park facilities now stand on the former sites of historic quarantine buildings, including the café and patio (once the Chinese barracks, #18–19), restrooms and bike rental (formerly the attendants’ quarters and bath house, #20), and the passenger loading area (site of the sterilizer building, #21). Photo credit: AIISF.

Annual Report of the Supervising Surgeon General of the Marine Hospital Service of the United States, 1896.

Cumming, Hugh S. "The San Francisco Quarantine Station," California State Journal of Medicine, Volume 1, Number 11, October 1903.

Hunt, Fred A. "The Guardian of the Gate," Overland Monthly, Volume 49, Issue 1, January 1907.

Laughlin, Carlile. "The United States Quarantine Service at San Francisco," The Pacific Pharmacist, Volume 7 Issue 1, May 22, 1913.

NARA. "Angel Island, San Francisco Bay, California map," Office of the Post Engineer - Fort McDowell, September 3, 1942 (rev. March 15, 1946).

NARA. "Hospital Cove: Buildings, Structures, Utilities, and Miscellaneous Facilities," General Services Administration, March 1, 1950.

NARA. "Map of the Angel Island Quarantine Station," Assistant Surgeon of Quarantine, 1913.

San Francisco Call. "Liner Nile is in Quarantine; Disease Feared," November 12, 1912.

San Francico Chronicle. "Fair Oriental Maid to Study for Grand Opera Under Master in Paris," November 12, 1912.

San Francisco Examiner. "Quarantine Annoys Chinese Songbird," November 12, 1912.

Smith, Kingland. "Around the World for the Northwestern Miller," The Northwestern Miller, Volume 57, Issue 4, January 27, 1904.